How to Improve Your Mobility

Everyone wants to improve their mobility, but nobody ever wants to work on it.

Perhaps it’s because you don’t know how to improve your mobility.

Perhaps it’s because improving your mobility seems like an overwhelming task.

Perhaps it’s because you have limited gym time and getting a workout in seems like a more effective use of your time.

Perhaps it’s because you’re thinking about mobility in the wrong way.

Let’s start by defining mobility.

Flexibility — also called passive flexibility or passive range of motion — means you can access a range of motion through the use of an external force, like the floor, the wall, a partner, a weight, etc.

Mobility — also called active flexibility or active range of motion — is the ability to control your joints and muscles throughout your range of motion, meaning you can contract your muscles through that range of motion.

Mobility = strength. The only difference between mobility training and strength training is that mobility training occurs at your end range, and most strength training doesn’t — hence why mobility training can feel so icky, especially if you’re not used to it.

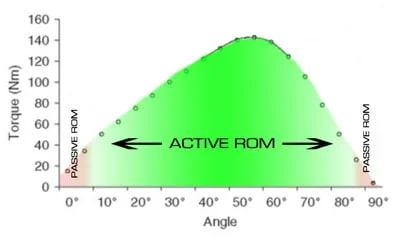

Take a look at the graph below…

Image by Functional Range Conditioning

The graph shows that muscles are able to create peak force at the midpoint between two joints. At the end range on either side, the muscles are able to create the LEAST amount of force, meaning that you are weakest and most susceptible to injury at the end ranges. If you are able to increase your strength at those end ranges, you not only lower injury risk and/or mitigate the severity of an injury, but you have more possibilities for movement because you are mobile throughout a larger range of motion.

The bigger the gap between your flexibility and mobility, the higher your injury risk. Injuries occur when there is too large of an imbalance, whether that’s an imbalance in stress levels, an imbalance in strength in different planes of movement, or an imbalance between flexibility and mobility. Almost all of us have an imbalance between the range of motion we can access passively, and the range of motion we can access actively, because most of us do not train near our end ranges of motion. This is good news — it means you have a big potential for mobility improvement!

Mobility training is training your nervous system.

When a particular area feels “tight”, it doesn’t mean your muscle(s) are actually shorter. Your muscles don’t actually change in length. The tightness is there because your nervous system is inhibiting the range of motion because it doesn’t trust you with that range of motion. Remember, everything your brain and nervous system do is in the interest of survival. The first thing it consider is that there could be a good reason for the tightness you are experiencing: perhaps you are or were injured, you’re hypermobile, or you haven’t earned the right to utilize that range of motion. To get rid of the tightness, you need to figure out WHY you are tight.

If the reason you’re tight is that you simply haven’t earned the right to use that range of motion, end range training can be used to override the nervous system and build strength so that over time, the nervous system will feels safe and allow you to access that range of motion at any time.

The tightness is there because your nervous system is inhibiting the range of motion because it doesn’t trust you with that range of motion.

So what’s more important: mobility training or working out?

I’d argue that mobility training and workout out can go hand in hand, or actually be the same thing. As I mentioned earlier, mobility training is just strength training at your end ranges. Working on improving end range strength and controlling the range of motion that you do have will make everything else you do work better and FEEL better. Mobility is the key to longevity and pain-free movement.

What’s the point of doing a hundred squats if your joints hurt while you’re doing them because you don’t have the necessary mobility?

I’d argue that everyone would be better off — from a health, fitness, AND longevity standpoint — by slowly and methodically training their mobility 2-3 times per week than by doing a 45-minute bootcamp class every single day that burns a 1,000 calories and leaves you sore as hell.

You’re probably wondering how to get started…

While there is no way for me to give you the perfect mobility program for you in blog post, I can give you some guidelines on what I believe is the best way to begin your mobility journey — a journey that is guaranteed to change your life (if you stick to it for more than just a couple of weeks).

Joint mobility

I used to think joint mobility was a bunch of baloney. I didn’t think it really DID anything, or burned any calories (this was back when I was a young, naive trainer who wanted to have a six pack and thought she knew something about something). Now I do joint mobility every single day; it’s the first thing I do when I wake up in the morning and often I do it several more times throughout the day.

Joint mobility can take many forms, but it generally means you are moving your joints in circles. Controlled Articular Rotations (CARs) —a term coined by Functional Range Conditioning — are a type of joint mobility where you take the joint through its full range of motion (a circle) while keeping tension throughout the rest of the body in order to isolate the joint you’re working on.

Think of CARs as a way to talk to your nervous system, and send the message that you would like access and control to the full capacity of your joint. “If you don’t use it, you lose it” rings especially true here: all of us lose range of motion as we get older, but we can do our best to mitigate the loss by taking each joint through its full range of motion daily (or at least a few days a week). Additionally, joint mobility is great for decreasing the gap between passive and active range of motion and increasing coordination and connection to the muscles around the joint.

A question I like to pose when expressing the importance of joint mobility: if you can’t control your joint range of motion while you’re simply standing or sitting down, what do you think happens if you move quickly or throw a weight over your head? Let me take a wild guess and say you’re likely to load a range of motion you can’t control, and cause damage to the joint which will wear it down over time. While some joint wear and tear is normal, wouldn’t you want to minimize that wear and tear so you experience less body pain as you get older and you can keep enjoying movement?

Here are a couple ideas for starting your joint mobility routine:

Spinal segmentation

Did you know that each vertebrae in your spine is a separate joint? Theoretically, you should be able to articulate each one individually if you practice enough. If your spine doesn’t work, nothing in your brain or body works, so keep that in mind when thinking about the importance of moving your spine.

Good morning routine (from Functional Range Conditioning)

This total body CARs routine takes you through joint circles for every joint, and works great as a warm up or a daily routine when you wake up (hence the name). The slower you go and the more tension you create, the stronger the message that will be sent to your nervous system.

Joint mobility routine, check. What do I do now?

Having a joint mobility practice is just the beginning of your mobility journey, although a rather essential one since it will increase brain-body connection and maintain the range of motion you already have. If you want to increase your range of motion, however, joint mobility is not enough. For whatever joint you want to improve mobility, you need to figure out whether you actually need more range of motion overall, or whether you need to decrease the gap between your passive and active range of motion (flexibility and mobility).

Figuring out whether you have enough range of motion overall is based on whether you have enough range to do the things you want to do. Figuring out whether you have a gap between your passive and active range of motion can be done by testing yourself or having a friend help, although of course the most accurate way is to be assessed by a qualified practitioner.

If you need more range of motion overall, you can proceed in a few ways.

Increase your flexibility by using external forces to put you into a position you don’t currently have access to, and then do isometric, concentric, and eccentric strength training exercises in that range of motion to create mobility.

Combine the two into one by following the FRC protocol of using Progressive Angular Isometric Loading (PAILs) and Regressive Angular Isometric Loading (RAILs), which means doing two isometric contractions at end range: one on the lengthened tissue, and one on the shortened tissue (in other words: contract in the OPPOSITE direction you’re trying to increase your range of motion in, then contract in the direction you’re trying to increase your range of motion in).

If you need to decrease the gap between passive and active range of motion, follow strength training principles.

Perform isometric, concentric, and eccentric strength training exercises in the range of motion you want to capture using progressive overload principles. Some of my favorite ways to do this include getting into a passive stretch and isometrically contracting the muscles there, using sliders for eccentric loading, and stall bar exercises.

Follow the FRC protocol for passive end range holds, hovers, and lift offs (pretty much exactly what they sound like).

How long does it take to improve mobility?

You don’t get strong by doing one set of squats.

You don’t become a marathon runner by running one mile.

Rome wasn’t built in a day. It’s going to take time to get mobile, just like it takes time to get strong. Or skilled. Or educated. Anything that’s worth doing is going to take work and consistency, and you’re going to have to do that work consistently FOR A LONG TIME.

I like the way my coach and friend Hunter said it: people overestimate where they can be in a year, but they underestimate where they could be in five years.

I like the way my coach and friend Hunter said it: people overestimate where they can be in a year, but they underestimate where they could be in five years.

Take my advice with a grain of salt.

I hope the information above was helpful for you in understanding mobility training and perhaps viewing it in a different light (it’s strength training, people!!). Maybe it will motivate you to start your own joint mobility routine, or experiment with end range strength training.

You should question everything in life — including this article — so feel free to experiment and see what works FOR YOU. While I generally follow the principles of the FRC system for myself and my clients, I don’t think it’s the end all be all for mobility training. There are plenty of other ways to improve your flexibility and mobility that do not follow the exact FRC process.

If you have any questions about mobility, please comment below.

To set up a mobility consult with me, email info@kbfitbritt.com.

There is plenty of science to back up what I talked about in the article above, and I’d encourage you to learn more by checking out Functional Range Conditioning.